By Dr Meghan Leaver, Co-Founder, PEP Health

Over the past two decades, the prevalence of obesity in the UK has increased, and it is predicted to continue to rise by 2050. Despite the prevalence of obesity, a longstanding issue has been access to services and care, which has been identified as a key priority to be addressed as part of the government’s obesity strategy. The government’s prioritisation of obesity has been underscored during the coronavirus pandemic - research evidence has revealed the higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 for people living with obesity. However, while much of the discourse around reducing the prevalence of obesity has focused on individual willpower and choice, much less has been said about equality of access, quality of care and other factors that may be detrimental to the progress made by those living with obesity and overweight disease conditions.

As we know, ensuring that patients have high-quality, equitable experiences in healthcare is a priority for the NHS, with significant media and public attention placed on reducing the negative impact of prejudice, discrimination and inequality of access across the health and care sector. Equally, the issue has been recognised in the NHS Long Term plan1, which makes a commitment to a more concerted and systematic approach to reducing health inequalities and addressing unwarranted variation in care. This is an important step, and one that is well overdue, but it is important when we think about inequalities, we are not just thinking about the overtly serious issues of racial and socio-economic disadvantages, but that we are also thinking about weight.

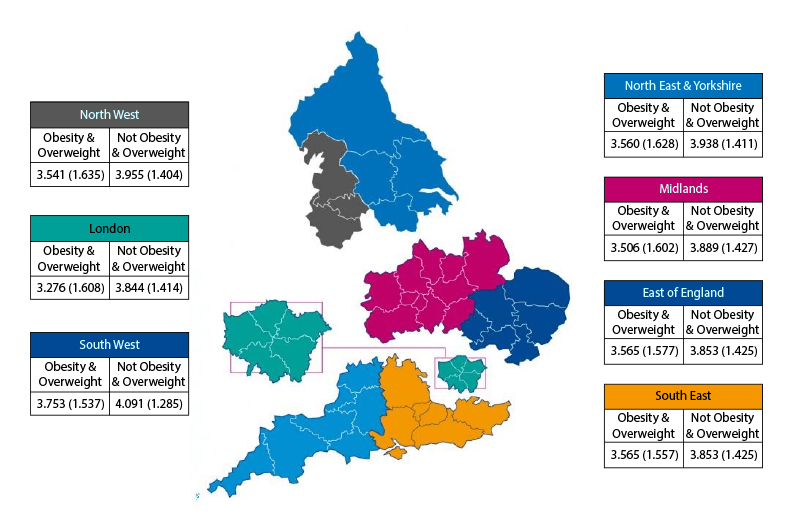

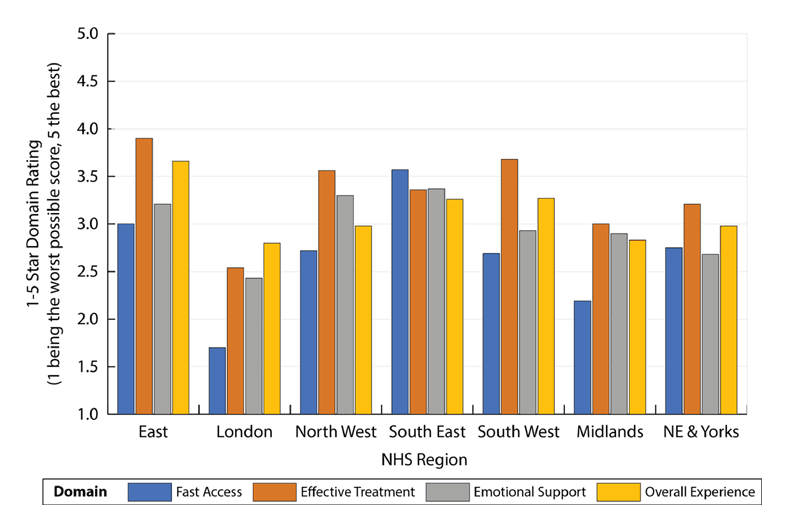

A study published by the Lancet2 journal of E-Clinical Medicine, using information gathered by PEP Health3 from NHS UK, Google, Facebook and Twitter comments, revealed that people who identified as being overweight or living with obesity had significantly lower perceptions of the quality of care they were receiving compared with those who didn’t. Further to this, the report highlighted the barriers to good quality care experienced by people who identified as living with obesity which included the speed of access, effective treatment, and emotional support, with stigmatising healthcare experiences also reported. Clearly, there is an issue; the NHS is not weight-inclusive.

Experience of weight stigma can lead to avoidance of future healthcare, lower trust in healthcare professionals, reduced quality of care and increased health disparities. It is also well-known that experiences of weight stigma and discrimination are associated with physical and mental health concerns such as lowered self-esteem, depression, and increased cardio-metabolic risk factors. Not only do these experiences fall out of line with NHS values, they are wholly counter-productive for a government and healthcare system actively trying to cut obesity rates, with so far limited success.

A significant factor in the report’s findings is the ‘postcode lottery’ that exists across the NHS, with levels of provision differing from region to region, leaving thousands of overweight and obese patients unable to access vital services and treatment. An inability to access services on an equal footing is patently unfair, but it also presents a continuing health risk for patients, which will end up costing the NHS more money than it would do to level the playing field. So, why isn’t more being done?

The same can be said for educating health and care professionals to provide accurate and informed health advice to patients. Evidence shows that people are more receptive to health advice from a trusted health professional, yet as a [recent King’s Funds report](https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-07/Tackling obesity.pdf)4 explains, many health professionals are deeply uncomfortable or unwilling to have conversations about obesity and, for some, unconscious biases affect how they work with obese patients, as reflected in PEP Health’s findings.

Concerningly, the risks of overweight and obesity disease conditions also disproportionately affect people from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This can be attributed to a number of reasons, including the increased prevalence of processed food outlets in lower income areas, access to green space, and the higher cost associated with healthy eating. There is clearly a much deeper problem than individual willpower and choice to make healthy choices. Ultimately this needs to be addressed, alongside better access and support, with policy that empowers people to live healthier lifestyles on a more granular level.

We have already seen positive steps in this regard, with the NHS Long Term Plan setting out plans to improve weight management services, both for individuals with the greatest need and for population groups in which obesity rates are higher. This commitment does need to be reflected across the board though, for all patients suffering from overweight and obesity disease conditions, who deserve equal and fair access to treatment, without stigma or discrimination.

Our findings were published in the Lancet and featured in the press on Eurek Alert and Mirage News.

1https://digital.nhs.uk/about-nhs-digital/our-work/digital-inclusion/digital-inclusion-in-health-and-social-care 2https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S258953702100420X 3https://www.pephealth.ai/ 4https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-07/Tackling%20obesity.pdf